The Fen-lands of Cambridgeshire

'The Fen-lands of Cambridgeshire' was published in Cambridge in 1883, it is one of an edition of 50 signed by the artist, this volume is no. 34/50. It is one of a series of large cloth bound folio books of etchings produced, covering areas of rural Cambridgeshire.

The etchings show scenes of everyday life across the Fens with Farren's observations and source texts from his research into the history of the landscape.

In his introduction, Farren writes ‘The etchings contained in this work are from sketches made during the past ten years and have been selected to shew the character and aspects of the fen-lands of my day. No part of the country has undergone such rapid changes as the great “fen-level”; and Cambridgeshire is the only county in which can still be seen the few remnants left from the great wilderness of bog and water, studded with islands, that formed the fens of the past, which have been described by an old writer as a watery waste “time out of mind, neither accessible for man nor beast, affording only deep mud, with sedge and reeds, and possessed by birds, yea, much more by devils.” These “deep mud beds” are now fields of golden grain, and sleek cattle everywhere graze under trees that have spung up where grew the feathery reed and sedge that once sheltered myriads of wild fowl.

No attempt has been made to idealise the subjects, and such scenes and objects have been chosen as will in many cases be sought for in vain but a few generations hence. They have been rendered with such faithfulness as will, I trust, make them of some value and interest in time to come.

Six of the larger subjects appeared in this year’s Etcher, the remarque proofs from which are included in the present work. Fifty signed and numbered copies form this edition.

December 1882’

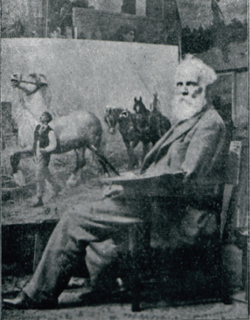

Robert Farren was an accomplished photographer and artist who worked across a range of mediums and is well-known for his paintings and prints. He was born in Cambridge in 1832 and lived in the city most of his life, spending a short time away in Scarborough before returning to Cambridge. Early in his career, he worked at the Sedgwick Museum as Assistant to Professor Adam Sedgwick and eventually went on to set up Farren Brothers photographic studios in Cambridge and Chatteris in the 1860s. Over the years he produced a large cataloue of works, from etchings and watercolours to large oil paingings. All but one of his seven oil paintings in public ownership reside with the University of Cambridge, these include portraits of famous alumni including the Director of the Sedgwick Museum, Adam Sedgwick, and also a Jurassic scene which is on display in the Sedgwick Museum. Wisbech & Fenland Museum holds a collection of nine of his large cloth bound books. Some of Farren's prints and books are held in public collections but remain in private ownership.

Robert Farren

The Cambridge Graphic, 1901.

The Cambridgeshire Collection,

Cambridge Central Library

Collection highlights

Click on the images in the gallery below to enlarge

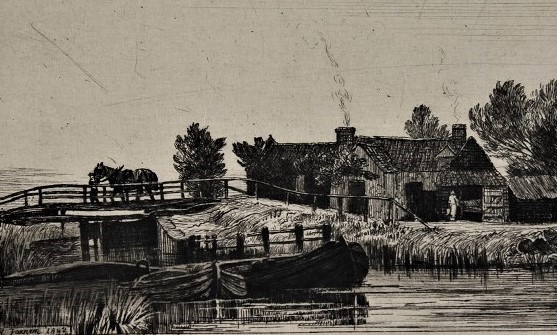

Bridge over the Lark

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

River Ouse at Littleport

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

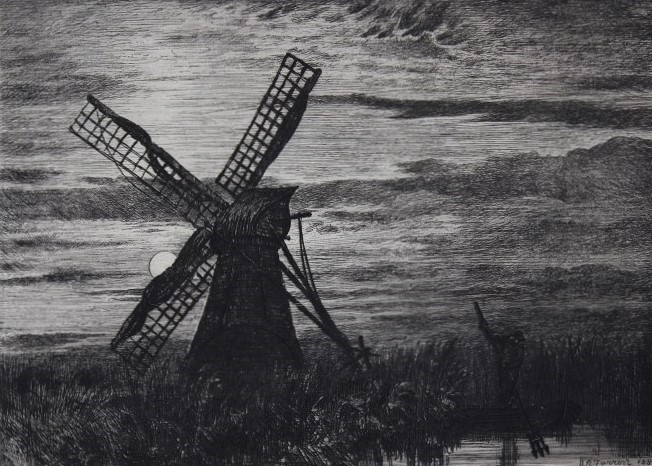

Mill at Somersham

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

River Cam at Clayhithe

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

Borders of Wicken Fen

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

Wicken Fen

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

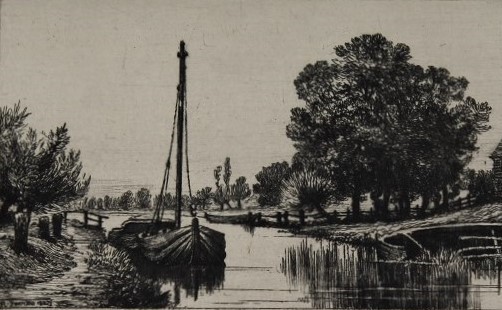

Burwell Lode, Upware

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

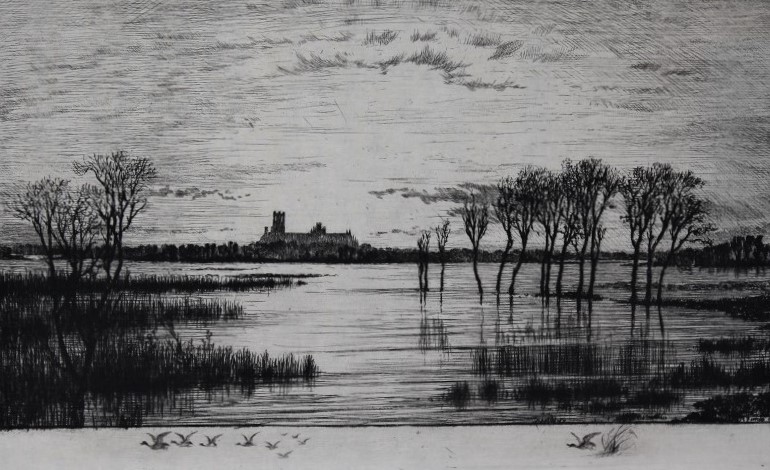

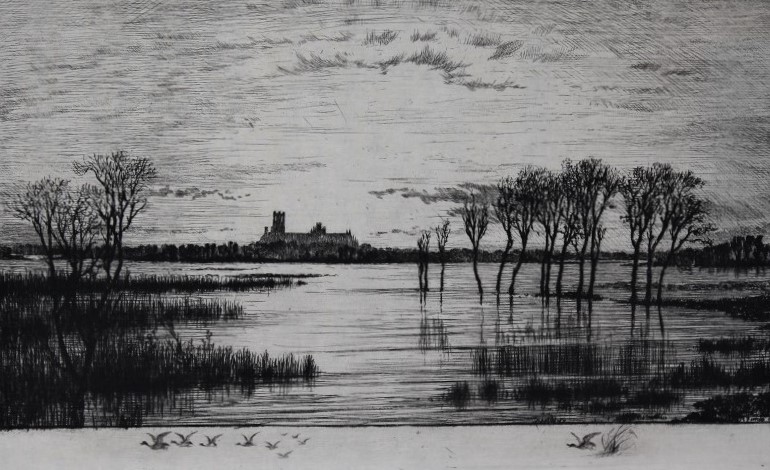

A Flood in the Fens

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

Peat Digging

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

Burwell Peat Fen

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

A Jump, Bank of the Cam

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

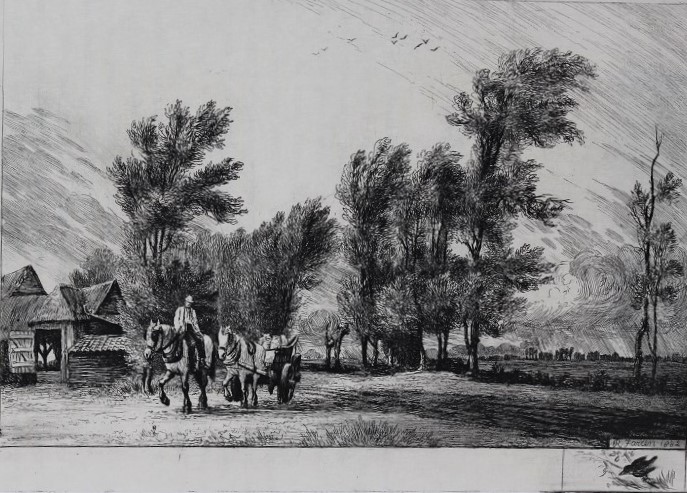

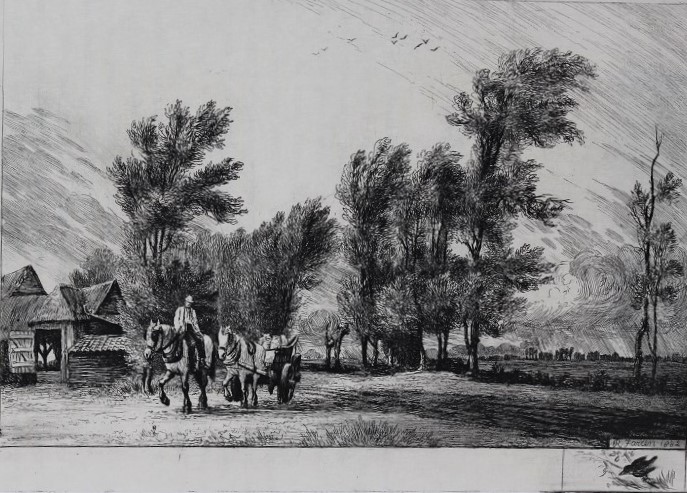

Drove-Way, Somersham

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

Sedge Cutter going to Work

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

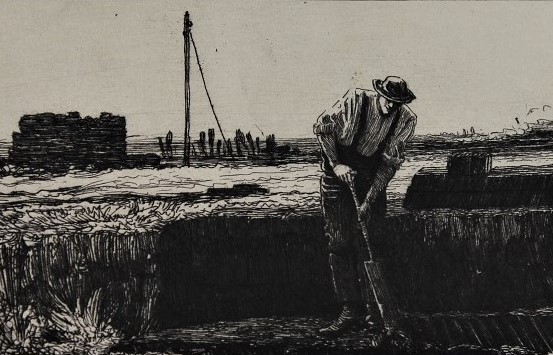

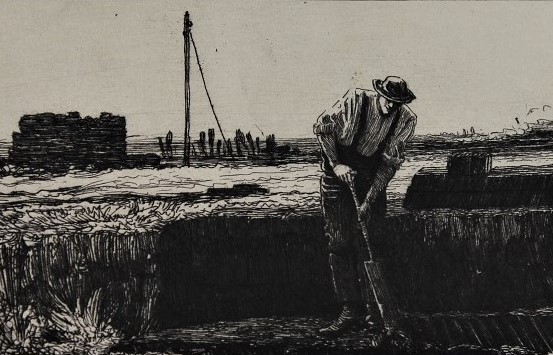

Hand-Ploughing

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

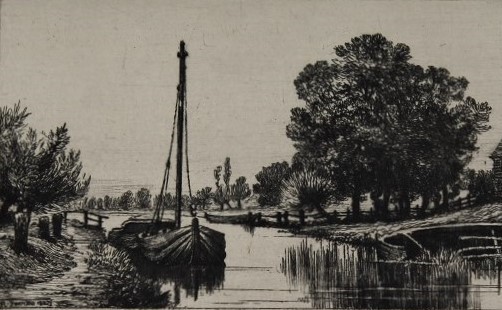

Bottisham Lode

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

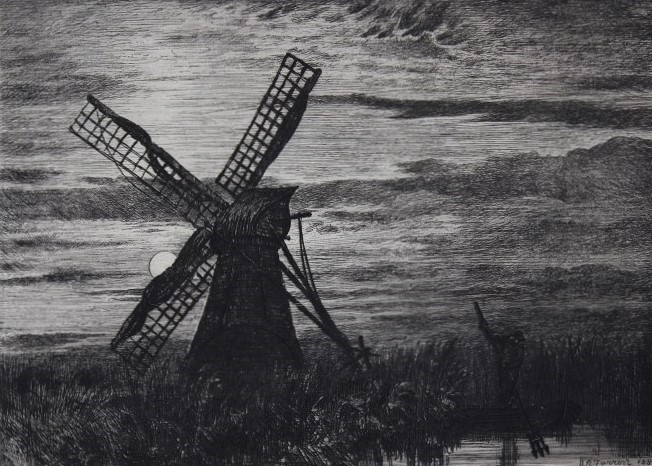

Mill at Waterbeach

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

Bridge over the Lark

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

‘The bridges that originally spanned the fen rivers were for the most part built of timber; but of late years these wooden bridges have been nearly swept away, and brick and iron have taken their place. Two of the old build still remain at Littleport, -one over the Ouse, and a smaller one over the Lark, at its junction with the Ouse; solemn, sturdy, picturesque old fellows, that have stood the brunt of a thousand floods, but will have succumb to the needs of a new generation, - for their days are surely numbered.‘

River Ouse at Littleport

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

Mill at Somersham

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

‘The picturesque ruin represented at the head of the Introduction stands in a field at Somersham, a solitary monument of man’s struggle with Nature’s forces, in which man has proved conqueror, of the bed of the river into which it once beat it waters is now a dry grass-grown channel.’

River Cam at Clayhithe

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

Borders of Wicken Fen

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

‘About twelve miles north of Cambridge there are two hundred acres of uncultivated wilderness bordering Wicken, called Wicken Sedge Fen. This primeval patch of sedge, reed beds and sallow scrub, a mere shred of his outer fringe, is perhaps the only bit left from the fen wastes of the past; cultivation and drainage have done their work, and the long vista mile upon mile, far as the eye can see, of corn and green pasture, was but a short time since such as this.’

Wicken Fen

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

‘A few more years, and this wilderness of sweet herbs and rare insects will have succumbed to civilisation, and will be growing “wheat and mutton” instead this happy hunting-ground of the naturalist, with its treasures, will have passed away for ever. Of the long lists of birds to be found in old books, excepting the smaller kinds, scarcely a representative is left; hawk, buzzard and kite are all gone; and of the flocks of water-fowl that once darkened the air, but a few moor-hen and snipe are left. But of insects an abundance may still be found, though may have disappeared within memory of man. The king of butterflies, the swallow-tail, still flits across the reed tops with rapid flight, or with expanded wings rivals the flower on which it thrones itself.’

Burwell Lode, Upware

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

A Flood in the Fens

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

‘From the silver thread meandering over beds of cresses and water-plants it becomes a turbulent swirling mass of discoloured water, filling from bank to bank, a source of no small anxiety to every one living near.’

Peat Digging

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

From the book ‘The Fenland Past and Present’ Farren quotes: ”at least 7000 years have elapsed since the climate was favourable for the growth of peat,”

“The peat lands possess distinctive features, which are very impressive. Not a town stands theron; the roads are perfectly straight; the landscape is as flat as the open sea; not a hedge-row breaks the monotony, neither does a tree appear, save in the long lines of tremulous aspens which skirt the main drains,” Farren suggests ‘ – and they should have added, “and drove-ways, or surround the lonely farmsteads.”’

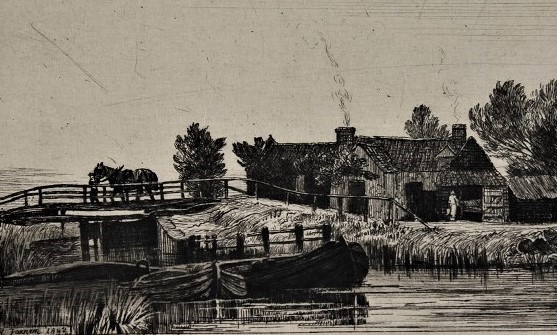

Burwell Peat Fen

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

‘After being left to dry for some days, the peat is stacked by the lode-side for conveying home by boat. Very picturesque and weird look these black peat-laden boats, gliding slowly down between the reed-fringed banks of the lodes in the dim twilight.

A great deal of peat is still dug for commerce from Burwell, Reach, and Swaffham fens, and sold in the neighbouring villages for fuel.’

A Jump, Bank of the Cam

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

‘The river banks (byways peculiar to the fen-lands), from their straight elevation affording glimpses of winding river and distant landscape, are always delightful; the flat places between bank and river, rich in rank grasses, provide plentiful pasturage for the numerous cattle that graze knee-deep thereon, or sleepily congregate about the “jumps” that are erected as barriers at intervals of a few hundred yards. They are probably so called because the barge-horses have to jump them, there being no gates. Everywhere along these miles of river-banks the artist will find good Dutch-like subjects for his pencil.’

Drove-Way, Somersham

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

‘This particular farm from which the sketch … is taken is a large one at Somersham, of which a thousand acres are devoted to potato-growing. Nothing can be more stirring than the scene in one of these potato-fields during harvest-time.’

Sedge Cutter going to Work

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

‘The sedge that grows here, in greater or les quantities as the seasons may determine (wet seasons being the most favourable to its growth), is cut all year round, except during frosty weather, and carried away in the barges down the lodes that bound and intersect the fen, to be sold to brick makers for covering unbaked bricks, or to be used as kindling in the surrounding villages.’

Hand-Ploughing

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

‘The ploughman wears an apron of sacking or leather, quilted, and bound down on each side with pieces of tough wood about as thick as a walking-cane, against which the cross-handle of the plough is rested; it is then thrust forward two or three inches deep in the soil, and turned over with a jerk at about the distance of every eighteen inches. The land is afterwards freed.’

Bottisham Lode

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

Mill at Waterbeach

Robert Farren, 1882.

Etching on paper.

‘Perhaps the most striking feature in a fen landscape (after the sky) is the Windmill. Mills wer first erected for drainage purposes about 1678., for we find that in consequence of the drains being inadequate to the purpose assigned them, “for the speedier cleansing and scouring of draynes, the four surveyors of the Level do forthwith buy each of them a mill, made for that purpose.”’

Our thanks to the Esmée Fairbairn Sustaining Engagement with Collections Fund for funding the development of this area of our website and making this exhibition possible through our digital collections strategy project, New Conversations.