The start of European slave trading in Africa by the Portuguese.

Thomas Clarkson

28 March 1760 - 26 September 1846

Thomas Clarkson was one of the main architects of the anti-slavery movement and led an extraordinary campaign against the trade.

Read on to explore more about Thomas Clarkson and his life.

Early Life

He attended Wisbech Grammar School and later became a student of St. John’s College Cambridge where, in 1784, he won first place in a Latin essay competition about slavery.

With the help of his brother, John Clarkson, the essay was translated into English and expanded into a book. It became the first publication criticising the slave trade to reach a wide audience and it made him a minor celebrity. His publisher introduced him to other prominent figures with similar views and a committee of twelve was soon formed with Clarkson as their leader.

This established the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, the first non-denominational anti-slavery organisation in Britain. The main aims of the Society were to raise public opinion and to lobby MPs to the point where Parliament would be forced to change the law.

The slave trade

The 'Middle Passage', which took the enslaved Africans from Africa to the Americas, was only one stage of a highly profitable, triangular trade route.

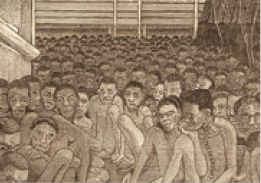

Ships loaded with European-made goods sailed to the West coast of Africa and exchanged their cargoes for enslaved Africans. These were transported, in over-crowded and horrendous conditions, across the Atlantic to be sold for luxury goods which were then brought back to Europe.

Many profited from this trade, not only ship and enslaved African owners, but also the manufacturers of the goods that were exchanged for the enslaved Africans. The legacy of this is still evident. Many of Britain's greatest institutions were created with wealth derived from slavery and the ports of Bristol and Liverpool acquired their economic importance and municipal splendour as a direct result of their involvement in the slave trade.

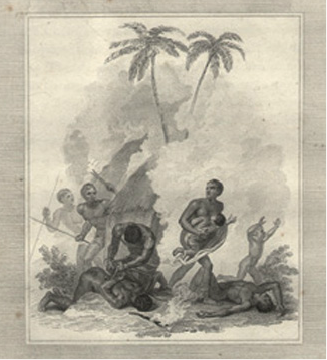

Capture of Slaves, from The Abolition of the Slave Trade, a Poem, in Four Parts by James Montgomery, 1814

Campaign techniques

To gather evidence against the slave trade, Clarkson rode 35,000 miles, interviewd 20,000 sailors and collected many items which he kept in a specially-made chest.

The chest contained many items that demonstrated the cruelty of the slave trade, such as handcuffs; leg-shackles; thumbscrews; whips and branding irons.

It also contained seeds, textiles and other goods from Africa which lent support to his argument that it was better to trade in goods than people.

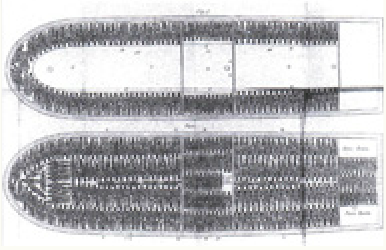

Clarkson observed that the publication of a plan showing the inhumane way in which enslaved Africans were packed onto a slave ship influenced public opinion more than mere words alone. He quickly realised that the contents of his chest might help to reinforce the message of his anti-slavery lectures. The chest became an important part of these public meetings and is often shown in pictures of him. It is an interesting object in its own right, both as an early example of a visual aid and as a travelling museum.

Clarkson's Chest and some of its contents. Credit: Sarah Cousins

Influencing public opinions

Thomas Clarkson helped to develop the prototype for modern campaigns to influence public opinions.

He travelled the country setting up 1,200 branches for the abolition of the slave trade and regularly corresponded with 400 people in order to create a mass anti-slavery movement. Many petitions with huge numbers of signatures were organised and presented to Parliament (519 in 1792); letters were written to local and national papers; and 300,000 people were persuaded to boycott slave-produced sugar.

An important part of the campaign was the lobbying of MPs and relationships were cultivated with those who were sympathetic to the views of the abolitionists. One such MP was William Wilberforce and it was Clarkson who eventually persuaded him to become the spokesman in Parliament for the abolitionist movement. With his brilliant speeches in the House of Commons, it was Wilberforce who came to be most associated with the campaign for the abolition of slavery, but it was Clarkson who provided him with a continuous supply of evidence for the speeches.

over 300K people were pursuaded to boycott slave-produced sugar

over 500 petitioins were sent to Parliament in 1792

William Wilberforce

An important part of the campaign was the lobbying of MPs and relationships were cultivated with those who were sympathetic to the views of the abolitionists.

One such MP was William Wilberforce and it was Clarkson who eventually persuaded him to become the spokesman in Parliament for the abolitionist movement.

With his brilliant speeches in the House of Commons, it was Wilberforce who came to be most associated with the campaign for the abolition of slavery, but it was Clarkson who provided him with a continuous supply of evidence for the speeches.

Josiah Wedgewood, from The Life of Josiah Wedgewood by Eliza Meteyard, 1866

Parliamentary campaign & 1807 Act abolishing the slave trade

Thomas Clarkson was only one of many important figures involved in campaigning for the abolition of the slave trade.

They included prominent politicians such as William Wilberforce, the MP for Hull; major manufacturers and industrialists such as Josiah Wedgwood; and leading figures from the arts including Hannah More the playwright and the poets Wordsworth, Cowper and Coleridge. Many also had strong religious beliefs and were Quakers or evangelical Christians.

Some had first-hand experience of slavery.

John Wesley – the founder of the Methodist church, had met enslaved Africans on plantations when preaching in Georgia.

Zachary Macaulay – one of the leading members in the parliamentary campaign, had been an assistant manager on a sugar plantation in Jamaica

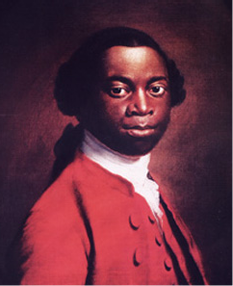

Olaudah Equiano (Gustavus Vassa) – had actually been an enslaved African. He leart to read and write a book, bought his freedom, became a sailor and eventually setlled in London where he wrote his autobiography. The book became a huge success and he toured England promoting both it and the abolitionist cause. He played a key role in raising public awareness about the slavery issue, but unfortunately did not live to see it abolished.

Olaudah Equiano (Gustavus Vassa), painter unknown, reproduced by kind permission of the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter

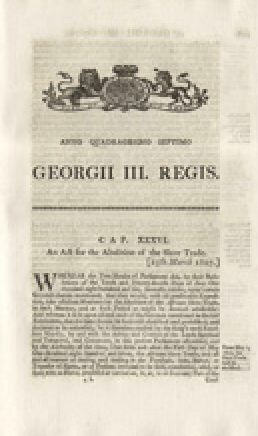

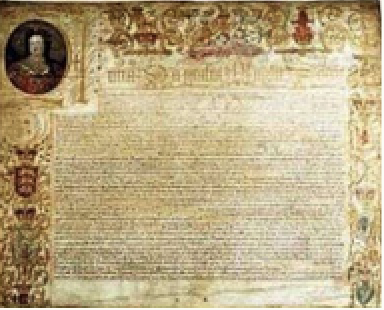

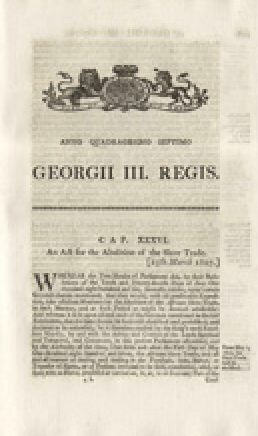

The passing of the Slave Trade Act in 1807 was not achieved without a long struggle.

Many had strong financial reasons for allowing slavery to continue and parliamentary legislation was blocked or defeated several times.

From 12th May 1789, the date of Wilberforce's first parliamentary speech against the slave trade, it was almost eight years before Parliament finally passed an Act aboloshing it.

A major part of this achievement was due to James Stephen, a new member of the Abolition Committee. As a leading maritime lawyer he helped to write a more acceptable form of abolition legislation and to steer it through Parliment. Luck and events also played a part. In 1800, the Act of Union allowed one hundred Irish MPs to enter the Commons, most of whom suported the Abolitionist cause.

The chances for abolition became even more favourable when Lord Grenville, who was extremely sympathetic to the views of anti-slavery campaigners, became Prime Minister after the death of William Pitt in 1805. The Act was finally passed on 23rd February 1807 by 283 votes to 16, but only after a ten hour debate which lasted until four o'clock in the morning.

Front page from the Act abolishing the slave trade

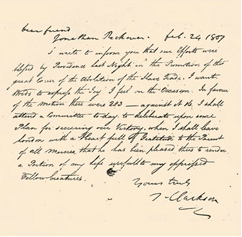

Letter from Thomas Clarkson to Jonathon Peckover informing him of the passing of the bill aboloshing the slave trade

Slavery and abolition timeline

1441

On Board Slave Ship, Fred White 2007

1492

Christopher Colombus crosses the Atlantic and discovers the West Indies.

1562

John Hawkins becomes the first known English sailor to obtain slaves in Africa and sell them in the West Indies.

1580

Sir Francis Drake completes his circumnavigation of the world.

1588

The Spanish Armada.

1627

Barbados becomes the first English colony in the Caribbean.

Slave Ship, from The Abolition of the Slave Trade, a Poem, in Four Parts by James Montgomery 1814

1641

English slave trade to Barbados begins.

Capture of Slaves, from The Abolition of the Slave Trade, a Poem, in Four Parts by James Montgomery 1814

1642

The English Civil War.

Oliver Cromwell

1660

Charles II charters the first English state-sponsored slave trading company.

Portrait of King Charles II, by Sir Peter Lely

1666

The Great Fire of London.

1671

A group of Quakers visit Barbados and suggest that the slave-owners treat their slaves with humanity and attempt to convert them to Christianity.

George Fox, Founder of the Quakers

1707

The Act of Union unites England and Scotland under the name of Great Britain.

1775-83

The American War of Independence.

Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851), Emanuel Leutze

1784

Thomas Clarkson wins prize for his anti-slavery essay.

1787

Anti-Slavery Committee set up, Thomas Clarkson commences fact finding missions, visiting Bristol and Liverpool.

Items from Clarkson Chest

1789

The French Revolution.

1790

Wilberforce's parliamentary motion to abolish the slave trade is defeated. Sugar boycott in England.

1792

The House of Commons votes in favour of abolition.

Plan of the 'Brookes', used by Abolitionists to illustrate the overcrowded conditions of slave ships

1805

The Battle of Trafalgar.

Lord Admiral Nelson

1807

Parliament abolishes transatlantic slave trade.

Front page from the act abolishing the slave trade.

1834

Parliament outlaws slavery in all British possessions.

1838-40

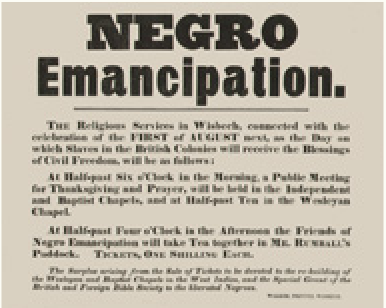

The end of the West Indian apprenticeship system brings full freedom for slaves.

Set of medallions commemorating the Anti-Slavery Convention, 1840

Later life campaigning and legacy

The passing of the 1807 Slave Trade Act did not put an end to slavery and Thomas Clarkson continued to write and campaign against slavery until the end of his life.

He concentrated his efforts mainly on furthering the campaign internationally and as part of this he twice met the Tsar of Russia, Alexander I. In 1839 Clarkson was elected first president of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. One of its first acts was to organise an anti-slavery convention and as its principal speaker he received a standing ovation from the delegates and observers from nine countries. Thomas Clarkson became a pacifist in 1816 and, together with his brother John, became a founder of the Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace.

Legacy

For the last thirty years of his life he lived at Playford Hall in Suffolk and when he died in 1846 he was buried in Playford at St. Mary’s Church. Wisbech commemorated him by erecting the Clarkson Memorial and by naming a school in his honour. In 1996 a tablet dedicated to him was unveiled in Westminster Abbey. Its inscription reads ‘A Friend to Slaves’.

Tsar Alexander I Staffordshire bust from the collection of the Wisbech and Fenland Museum

The unveiling of the Clarkson Memorial in Wisbech, 11 November 1881

Artefacts at the museum

Thomas Clarkson's chest

Thomas Clarkson's chest

Daggers

Leather bag

Woven textile

Lieutenant John Clarkson, R.N, aged about 27

John Clarkson

John Clarkson, Thomas's younger brother, also played a significant part in the history of the anti-slavery movement.

Born in Wisbech in 1764, he joined the Royal Navy at thirteen as a midshipman and fought in the West Indies during the American War of Independence. Perhaps as a result of what he saw there, at the end of the war he joined his older brother in campaigning for the abolition of slavery.

Migration leader

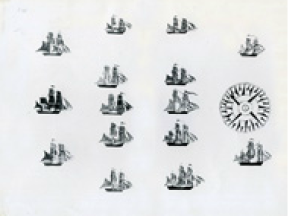

When someone was needed to organise and lead the migration of 1,192 ex-enslaved Africans to a new colony in Africa, John Clarkson’s background and experience made him the ideal candidate. The enslaved Africans had gained their freedom in return for fighting for Britain during the American War of Independence and were initially resettled in Canada. The government, however, failed to honour its promises of land and in order to survive many were forced into a form of slavery. John successfully gathered the ex-enslaved Africans in Halifax, Nova Scotia and arranged the fitting out of fifteen ships for the journey across the Atlantic. After their arrival in Sierra Leone, he served for ten months as the superintendent in charge of the colony before returning to England.

John Clarkson's drawing of his fleet that took the ex-enslaved Africans back to Africa