Charles Dickens

7 February 1812 - 9 June 1870

Charles Dickens was brought up in poverty and was very critical of the class divisions of Victorian England. His novels often contain a ‘rags to riches’ theme. However, Dickens is cynical about the effect of money, as in the case of Great Expectations.

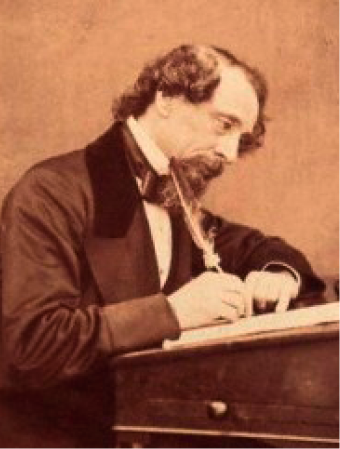

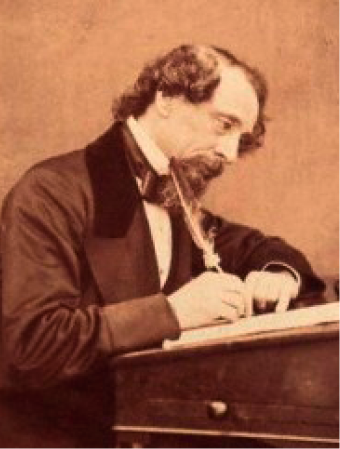

Dickens by Herbert Watkins, 1858

Great Expectations

Great Expectations was first published in the weekly journal All the Year Round and the opening instalment appeared on Saturday 1st December 1860.

'A Rubber at Miss Havisham's' by Marcus Stone

Dickens by Herbert Watkins, 1858

The story

Great Expectations tells the story of Pip a young orphan who lives with his older sister and her husband Joe, a blacksmith.

Pip visits his parents’ graves on Christmas Eve night where he stumbles upon the escaped prisoner Magwitch, who terrifies Pip into making good his escape.

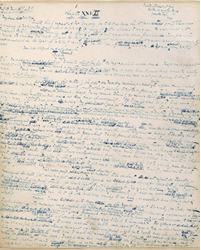

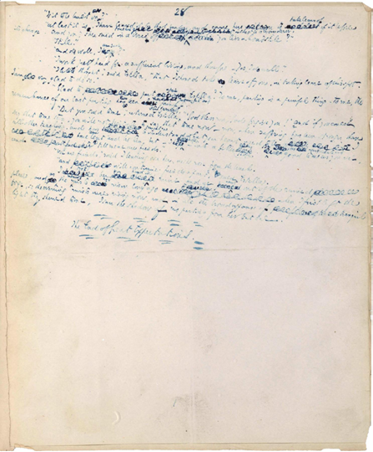

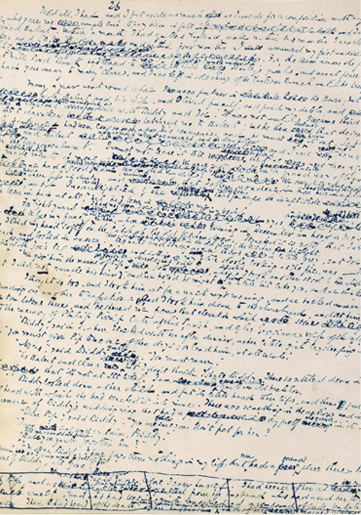

Great Expectations first page

Reverend Chauncy Hare Townshend (17981868). A portrait in oils by J Williamson after J Boaden

1868

Great Expectations and Wisbech

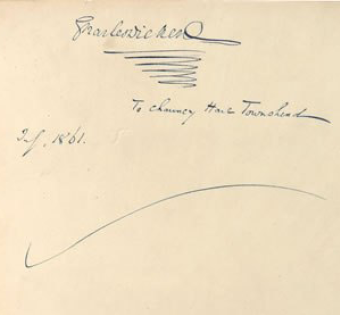

The original manuscript of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations was bequeathed to Wisbech and Fenland Museum by the Reverend Chauncy Hare Townshend in 1868.

1798

**Born in Godalming in 1798, Townshend came from a family with estates near to Wisbech.** During the 1830s Townshend suffered a bout of illness which led him to develop an interest in Mesmerism. Among those who also had faith in the practice was Charles Dickens, who had been introduced to it by Dr John Elliotson, who was a leading practitioner of the art. Dr Elliotson introduced Dickens and Townshend in 1840 and a lifelong friendship ensued.

Dr John Elliotson (17911868)

The first page of the original manuscript of Great Expectations

Townshend painted, wrote poetry and had a keen interest in natural history and geology. As an avid collector of the decorative arts each of his houses had ‘the interest of an art museum’.

It had been suggested that Dickens’s affection for his friend and his maladies were charactized in the portraits of Cousin Felix in Dombey and Son and Mr Twemlow in Our Mutual Friend. Townshend published verse and in 1859 dedicated the Three Gates to Dickens. In return Dickens inscribed the bound copy of the manuscript of Great Expectations and gave it to Townshend in July 1861.

Bleaker ending

Originally Dickens conceived a different and bleaker ending for Great Expectations. His first ending had Pip and Estella meet briefly in London four years after Pip’s return from abroad and separating.

He was deterred from this ending after showing the proofs of the concluding chapter to his friend the novelist Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton. Lytton thought that the ending was too disappointing to the reader and suggested a happier ending with Pip and Estella remaining together.

Following this advice Dickens put to one side his original ending and wrote the ending which now appears in every standard edition of Great Expectations.

With Estella after all'.

Illustration by Marcus Stone.

Edward Bulwer Lytton (1803-1873).

Oil painting by Henry William Pickersgill.

Traces of the beginning of the original ending can be seen in the manuscript boxed and crossed through. Intriguingly, the very last line of the revised ending in the manuscript actually reads “I saw the shadow of no parting from her but one” the sinister “but one” now being dropped in the standard text of the novel.

Hover over the images of the manuscript pages to zoom in.

‘Mr Micawber’ from David Copperfield by Charles Dickens.

Sketch by Frederick Barnard, 1884.

A Petrarchan sonnet

This shabby shape is not the real me.

Imagine, please, neat-knotted round my throat,

A silken scarf beneath my winter coat

Not vulgar. I will give to charity,

Perhaps. My wealth won’t make a change in me,

Though change no longer has the need to float

In sweaty fists. A mansion with a moat

And helipad? My finer self’s beneath

My iceberg graph of debt outlined in red:

Under the waves, its bulk a reassuring

Black. You’ll understand, I’ll have to learn

New ways. I scrape the scratchcard foil and shed

My old abandoned skin. A roar of falling

A belching jackpot, gold with unconcern.

Elaine Ewart Fenland Poet Laureate 2012.

*‘Money is a great preoccupation in Dickens' novels. In his childhood, Dickens himself experienced the trauma of his family falling into serious debt, and famously endured a period of drudgery, working in a blacking factory, which had a profound effect on him in later life. In Great Expectations Dickens takes a practical view of the way a person's financial position dictates their opportunities. He does not idealise or demonise the possession of riches but explores the moral, social and psychological aspects of getting, spending and giving money. In today's economically uncertain times I think Dickens' unsentimental approach to wealth and poverty strikes a chord we can all recognise’.*

Dickens, c.1870

Dickens chronology

1812

Born on Friday, 7th February at Landport, a suburb of Portsmouth

1824

Father arrested for debt and imprisoned in the Marshalsea with family

Dickens put to work at Warren's Blacking Factory

1833

“A Dinner at Poplar Walk” published in the Monthly Magazine

1834

Becomes reporter on the Morning Chronicle. Adopts pen name Boz

1836

Sketches by Boz, published. Marries Catherine Hogarth

1837

The Pickwick Papers published. Birth of a son, the first of ten children

1838

Oliver Twist published. Visits Yorkshire schools of Dotheboys Hall type

1839

Nicholas Nickleby published

1841

The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge published

1842

First visit to North America, described in American Notes

1843

A Christmas Carol published

1844

Martin Chuzzlewit published

1848

Dombey and Son published

1850

David Copperfield published

1853

Bleak House published. First public readings from A Christmas Carol

1857

Little Dorrit published. Dickens falls in love with Ellen Ternan

1859

A Tale of Two Cities serialised in All The Year Round

1861

Great Expectations published in three volumes

1865

Our Mutual Friend published. Dickens in Staplehurst, Kent train crash

1870

The Mystery of Edwin Drood issued in 6 monthly parts (was to be 12)

1870

9th June

Dies, after collapse at Gad’s Hill Place. Aged 58

Wisbech & Writing

Historically Wisbech has a strong association with imaginative and factual writing.

William Godwin (1756 -1836) born in Wisbech, journalist, political philosopher and novelist.

Thomas Clarkson (1760 -1846), born in Wisbech, Antislavery campaigner and author.

William Hazlitt (1778 -1830) his father became pastor in Wisbech in 1764, Hazlitt was an English writer.

Rev. Jeremiah Jackson (1775 -1857) local vicar began a ‘regular series’ of diary volumes in 1812.

John Peck (1787 -1851) born Newton, near Wisbech. Kept a daily diary from 1814 until he died in 1851.

William Ellis (1794 -1872) Missionary and author. His family moved to Wisbech when he was four.

Octavia Hill (1838 -1912) born in Wisbech, social reformer.

William Digby (1849 -1904), born in Wisbech was a author, journalist and politician.

Rev. Wilbert Vere Awdry (1911 -1997), Vicar of Emneth, creator of Thomas the Tank Engine.

John Gordon (born 1925) is an English writer moved to Wisbech at the age of 12. Author of The Giant Under the Snow.

William Godwin

John Peck

Support our archive and research resources

To maintain and conserve our valuable resources, we need your contributions, please support us by donating today.